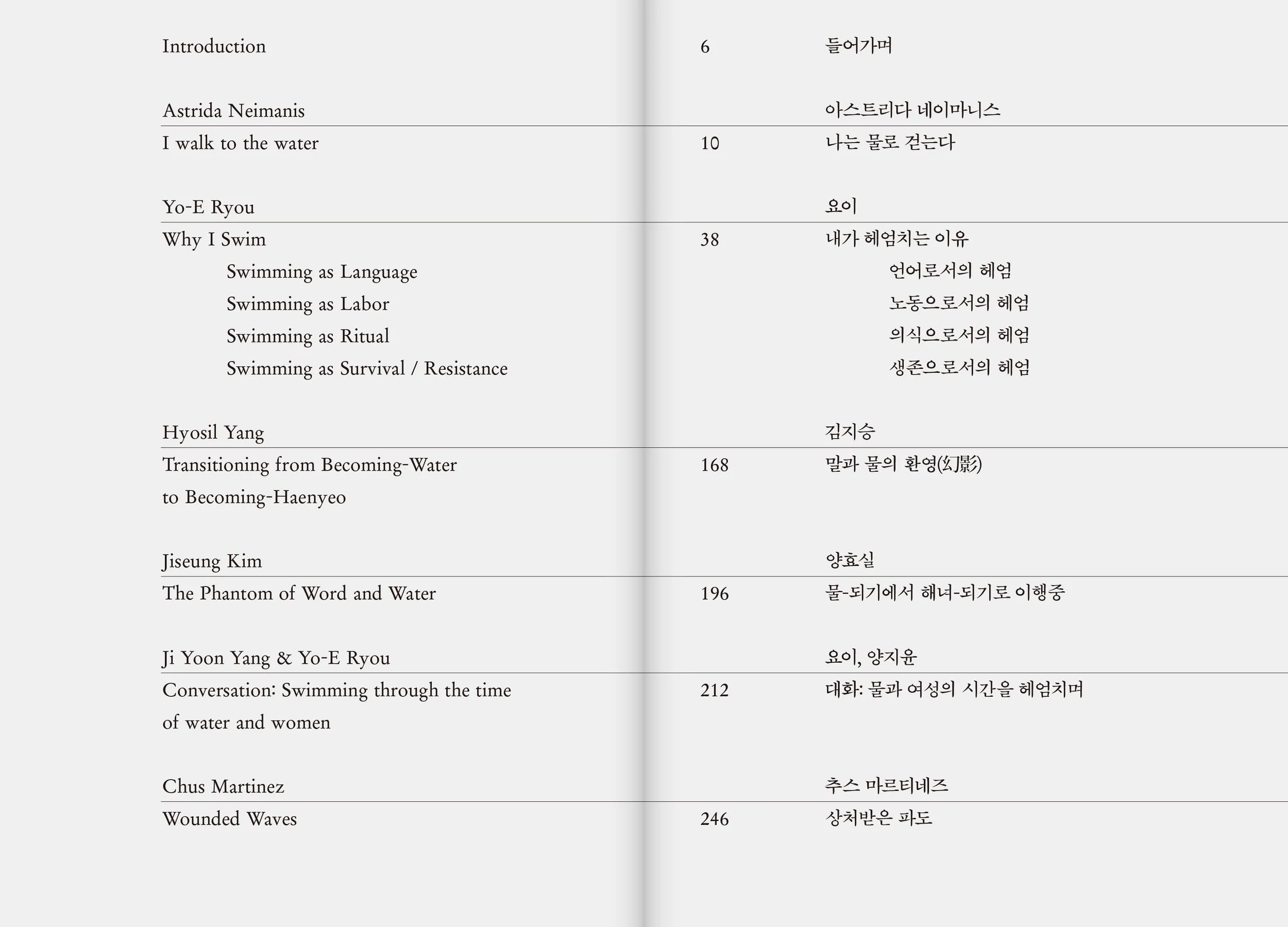

아티스트북 Artistic Research book

내가 헤엄치는 이유 Why I Swim

요이 Yo-E Ryou

사라져가는 제주 바다와 해녀들 사이에 스며들어 작가는 그들의 이야기, 그리고 그들이 바다와 공존하고 인간을 넘어선 존재들과 관계맺는 방법을 듣고, 쓰고, 나누며 물-되기를 실험한다. 작가가 물과 관계맺는 과정에서의 대화, 물 속에서 만난 자아와 이웃 여성들, 인간을 넘어선 다양한 종들과의 대화와 사유를 엮는다. 이것은 현대 자본주의와 기술이 지배하는 시대에 아직도 살아 숨쉬는 아름다우면서 모순되고, 고전적이면서도 급진적인 구전문화-몸에 배어있는 이야기들을 해석하고 이해해보려는 시도이다.

Immersed in the Jeju sea and the disappearing community of Jeju haenyeos, the artist explores ways of becoming-water while listening, writing, speaking, and remembering the lineage of the diving women and their coexistence with the bodies of water—more than human beings. This anthology attempts to weave the many different fascinating yet contradictory, ancient yet radical interpretations of orally transmitted practices still at work in our current world of capitalism and technology.

To be published in April 2025, by Mediabus, KR

—

후원 With partial support from :

- 제주특별자치도, 제주문화예술재단 Jeju Foundation of Arts and Culture, Jeju Special Self-Governing Province

- 이 책의 한영 번역의 일부 (말과 물의 환영, 물과 여성의 시간을 헤엄치며) 는 문화체육관광부와 (재)예술경영지원센터의 지원을 받아 번역되었습니다. Korean-English Translation of two essays in this book is supported by Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism and Korea Arts Management Service'

-

“ I walk to the water.”

It describes how I find my way into a new place by finding the water, and recounts a personal family story about walking to the water. It will also briefly describe some of the ‘walking to the water’ walkshops I have organized, and discuss the pull of the water.

-

There are also wounds on blades of grass,

there are also wounds on petals.These are the starting lines by Jeong Ho-seung’s poem, a very popular Korean writer. The acknowledgment of non human pain, of the possible wounds that nature may have, is still rare. Instrumental knowledge and the focus of human consciousness by Western philosophy approaches mades the pain of the non human world a void, a vacancy. We prefer to ignore than to carefully listen to the millions of signals that tell about this pain. We prefer to state that the absence of language makes it impossible to be certain. And yet, we know about this pain. We also know about our responsibility in causing it.

Does art really help?

Is art really able to make a difference in the crimes against nature?

It does. A crucial issue in our relationship with nature is learning to sense nature differently. Breaking the dualisms that define human as different from nature and going beyond the conventional assumptions that made human on top of the pyramids of power is a task. In the last decades, we have seen how art and artists took upon themselves the mission of listening to sentient life. This urge to explore how to open up our senses to stimuli and signals that we have not been receiving before has been described as „ecological“. But I would say this world impulse responds more to an epistemological adjustment. Indeed, we want to learn how to relate to nature differently not only because we want to reverse the damage we have done —and we are still doing to nature. The main goal is not pragmatic, but biological. We would like to become different as humans. We would like to become more natural, more animal, more able to be part of the world of life.

Is artificial intelligence natural?

Together with this urge to sense and to open up the human’s possibilities of sensing life that is unprecedented, another dualism appeared. Technology and programmed machines that are meant to go beyond the human emerge as a strong narrative. Humans see the power and the aspiration to reign over all forms of life almost as a mandate. To expand presents itself as a much powerful impulse than to understand. The human nature now is split into two. Those that open up to nature and those that embark into a new domination. The domination of artificial intelligence versus life.

Human imagination is powerful and, paradoxically, also poor. The creation of something bigger than us leads to an out-of-control power that may end up annihilating the species. Why so? Isn’t it possible to imagine artificial intelligence as being the greatest ecological intelligence that ever existed? But could we actually design and imagine machine intelligences to compensate human failings and inadequacies? Artists think so, and a part of the scientific community too.

The work of Yo-E Ryou can be seen as an exploration of how, a simple exercise, swimming, can entirely change our view on life. Swimming is in her work a poem, a manifesto, a revelation, an adventurous encounter, a deep and humble way of paying respect. Filmed in the Jeju island, home to the haenyeo, a community of women who dive into the sea to collect sea cucumbers, abalone, and seaweed as their profession. Yo-E Ryou is not one of them, she is one with them. Her performance in the sea is meant to affirm this difference and, at the same time, create a poetic and perceptional dimension to see their life-with-the Ocean under a philosophical perspective, as the gathering of an expertise that is ancient and relevant for those that live otherwise. Yo-E Ryou was one of those people living with her back to the Ocean. In the crowded cities, in our everyday routines, in the aspirations we culturally and socially we collectively develop, the Ocean is far. True. Among the things we would like to accomplish swimming in the Ocean is often not on the list. Our growing interest in immersion is paradoxical. In addressing totalizing environments one comes to think about technology and the possibility of being in an image bubble, in an infinity room. This desire to be inside is ancient, it awakes a sense of safety and togetherness while it also possesses an uncanny dimension. But before the Baroque mirror halls, the infinity rooms, and the totalizing technologies of today was the Ocean. The Ocean provides this feeling of immersion and together, it also provides a sense of rhythm that synchronizes with our body, our breath, our heart. But the separation between us and the Ocean is still impressive. We have the myths about the Ocean and, today, the facts and a growing social presence. But we still lack the methods, the development of simple and effective ways of introducing the ocean in our lives. Coastal societies —like Korea or Spain—also lack those methods. Living next to the Ocean only means that few dare to enter its sacred space to make a living. There are also haenyeo women in the place where I grew up in the northwestern coast of Spain. Women in charge of climbing the very dangerous cliffs and getting the precious and expensive barnacles. My grandmother was very afraid of the cold and dark Ocean, but she accompanied the group of women that dared into the cliffs. Very often the low tide was in the middle of the night. If it coincided with a bright moon the tasks were easier, if not a large number of women—like my own grandmother—hold an electric torch towards the stone walls where they were hanging. The winds in this part of the country nourish the waves in scary ways and often the danger of being knocked against the rocks and becoming unconscious was to be swallowed. Seafood is seasonal and if the winter is barnacle season, the spring months used to bring - and still do bring women - to the white sandbanks where there were thousands of cockles. The sale of cockles directly to the canneries and not in the fish market, like barnacles, brings less income but also less dangers. However, the long hours in the water crouching in a certain position and doing the work of digging up the mollusks and putting them in a net bag brings incredible injuries to these backs.

Works like this film and object installation created by Yo-E Ryou act as reminders of the important role of those that accompany the Ocean. If the haenyeo women continue to live by and with the Ocean in their everyday existence, generation after generation, we —all the others—need to find a way as well to reconnect with the Ocean. It is a mystery why many coastal communities do not know how to swim. One would assume that the inland people wouldn’t know how to swim but those living on the sea swim well. It is not the case in many, I would say, the majority of the coastal communities. It is also strange how there are not many texts written about this matter. In the case of some latitudes, you can attribute this lack of skills to the climate, or the difficulty of the coast, or the dangers of the currents. But even if you travel to warmer countries, such as the Caribbean or even the Solomon Islands, the populations there also do not swim. I assume certain religious and moral issues prevent people from swimming naked or almost naked. Showing the body is an issue and that issue may have been on the origin of avoiding the effort to teach the majority already in their childhood how to swim. One can also imagine that swimming with your clothes on —as Yo-E Ryouis doing in her video—can only be performed under great weather since, if a danger appears or an event occurs, wet clothes may be a hindrance and originate a problem.

I often think, though, that there are other reasons why we do not swim, why we are not at ease at the sea. The concurring and owning of the seas has been since ancient times a big quest by all the powers. Owning the sea, like now owning the virtual space, meant owning everything, since all territories float, theoretically on its waters. Owning the seas —connected and connecting— meant owning the routes, the trades, and the making of economies that tentacularly caress as many places as possible. The „discovery“ of the connecting routes between the Philippines and Mexico in 1565 by a Basque lawyer and seafarer changed the world. The Philippines became a huge hub connecting the goods produced mainly in Guangzhou, China with Mexico. Connecting China with Mexico meant connecting two of the biggest empires of the time—Portugal was the other. It is easy to imagine the Spaniards, accustomed to the coast and the routes of the Atlantic wondering about the vernacular skills possessed by the Chinese and Philippine seafarers and their very different sailing boats. Sailing long distances safely gave those people courage and knowledge about routes and ways of traveling unknown in Europe. However, the Spaniards forced the native male population to work in the shipyard of the Manila galleons in Cavity, south of Manila, and join their cargo ship culture.

I came to think that this ownership of the seas and its deeply cruel culture created a fear, a fear that has been transmitted through generations towards the salt waters. The spreading of the colonial empires could have contributed to the inhibition of swimming. Enjoying the Ocean as your own, as part of your culture, as part of your identity has been severely terminated by the colonial powers. This probably affected identity and also gender identity. Being your own boss in your own sailing boat has been replaced by being a slave, or precarious worker in a domination system. Indeed domination does not stop in the year the colonial powers stop having the same influence on the territories and the people. Domination continues like radioactivity, like a strange energy that survives and negatively affects the affection towards everything, the Ocean included. Domination stays as an uncontrolled fear that prevents us to enjoy and feel the waters as part of our own bodily waters.

When I was a child I thought the blue of the water was just a gigantic iris, a gigantic blue eye. We were all swimming in these beautiful blue as the artist is doing in her film, and while swimming we were all guarded by the Ocean eye. Blue eyes are not blue, as the Ocean itself is not blue. The blue is just the light merging with the liquid creating this beautiful effect of blue transparency. Thinking of the Ocean surface as a blue eye was a way to overcome fear. That blue is sustained by an intense amount of darkness, and we are all afraid of the dark. The Ocean is not dark though. It is only our incapability of seeing in the absence of light that makes the depths appear dark to us. Other eyes accustomed to inhabiting those salt waters and its depths for millions of years can see its wonders in full. Nature has created a system where skins and many living forms possess bioluminescence. Lighting bodies sending signals to other creatures and giving light in a world where the sun is not present.

In the video, we exactly see the surface and the swallow waters, and the very limits humans without much gear —like the haenyeo— can still perform. After that world other Ocean worlds follow but to enter into its depths, we humans will need assistance. The video situates us and in doing so it situates our humble condition as a species. We should be conscious of our capabilities and conscious about how much we are co-dependent on the Ocean.

Actually, swimming and floating on the surface is a wonderful way of experiencing our co-dependency. Colonial domination and all postcolonial capitalistic dominations love the fiction of us as a species alone. The human-hero that needs only itself to survive. Our minds suffer immensely from this fiction also because probably —unconsciously—our body and all its organs fight against this nonsense. We need the support of these waters, we need the salt in our body, we need the care of the sun, we need the food to survive, and we need the waves to breathe. Imagine the Ocean as the biggest mental health counselor that ever existed. Imagine its waters as a humongous swinging bed that cares about us breathing rhythmically preventing us from freaking out and starting to breathe abnormally, causing a shock to our whole body: panic. Imagine the Ocean as an anti-panic organic machine. Imagine us having wounds and the Ocean having wounds and being able to connect and share the pain while experiencing already its healing embrace. Nothing exists alone, nothing exists without a wound. The Ocean knows, we should be reminded.

-

The Phantom of Word and Water

Jiseung Kim

“(. . . ) Life is this unspeakable moment, a moment greater than the event itself.” - Clarice Lispector, Água Viva(1973)

Today, the weather is unseasonably cold and bright. In the middle of the room, my bag is wide open and I keep putting things in or out. The bag reminds me of a similar colored suitcase I saw in a movie last night, which carried the body of a murdered woman. Putting a cute rainbow sticker on one corner of my bag balances out this unsettling image. The place I am going to is windy and carries many things. The bag shouldn’t be too light or too heavy, and the items I place inside it shouldn’t be very old or very new. Clarice Lispector’s Água Viva finds its way into the bag. “Água viva," also known as “living water,” is impossible to measure. Will I be able to experience the fresh accumulation of water at every moment? I should keep my expectations neither too light nor too heavy.

Because her name has two “O”s, so she is listed as “OO” in my notes. The day I first received an email from her, I learned about another potential diagnosis, underwent additional tests at the hospital, completed two three-hour lectures in the afternoon and evening, ate a late dinner, fell asleep, and had a dream. In my dream, my body slowly dissolved into a liquid, starting from the tip of my toes, and gradually disappeared. The wet extinction felt painless. Adriamycin, Endoxanju, Thaksotel… I knew the names of the liquids that melted my body. It does not hurt when you know the names. Those who entered my body melted it from the outside. A specific memory faded away as it transitioned from the inside to the outside. The liquid wiggled. My body, which I thought had been melted away, remained in a transparent shape like jelly. ‘That’s not me,’ As I convinced myself again and again, I woke up from the dream. The letters from the OO’s invitation email to “islands in islands” fell on my bed like raindrops. I didn’t want to do anything. But I knew I had to do something at the same time—for example, relying on other women’s experiences to interpret my own. I wrote a reply to OO. Thank you for the invitation.

I have not decided what to pack yet. The bag opens its body wide, swallowing the time and spitting it out again. I could simply write, ‘Time has passed,’ but as I glance at the clock, I question the linearity of its passing. It is an old rumor that time moves consistently in one direction. It's not a time with gaps, limps, or locks, it's not a time that leaks or deludes, it's a time that flows from 0 to 9, and that remains a mystery to me. When Professor K mentioned that an infant must be able to endure frustration to measure time, I immediately grasped what she meant. Frustration arises from the absence of a loved one. We first become aware of time in our lives when we sense the interval between when our mother’s breast is present and absent. While the baby’s first object comes and goes, the frustration the baby feels from its absence may be an indication of time. A few years ago, when I encountered haenyeos in Yeongdo, Busan, I remember a Sangun(senior) haenyeo remarking, “multtae (tide time) means the coming and going of water,” as she sliced sea cucumbers in half. It is the moment between coming and going, a moment when waves flatten, the moment when exhale and inhale intersect. I want to spread a new rumor that the time of our bodies is like that.

The people I will be encountering on this trip are haenyeos, who live in a seaside village on Jeju island where OO lives. People who live in the time of water and speak a language that has traveled far and returned. Just thinking about it makes my heart race. I zip up my bag after placing Hélène Cixous’s The Third Body on the top. This bag will carry my uncontrollable body. All the problems, except for the one of transporting my body to the island, were on the island. I’m going, but it feels like they’re coming as well. I jot down the things that will soon come my way, like waves. Unusual waves.

Wave 1

In the projects I have carried out in collaboration with public institutions, they have been responsible for setting up the entire event, from promotions to invitations, and then assigning me a specific role. However, this project poses a different challenge as it was difficult to officially secure the participation of haenyeos. It is the tidal time that motivates them. Will it be possible to persuade them to attend the talk and keep their attention for an hour or two? After all, I am not water (nor oyster, alcohol, or rope).

Wave 2

I was told that the haenyeos had planned a few days of work at sea to catch some shellfish to sell at the annual Jeju Haenyeo Festival. However, they could only do the work if the weather and water conditions were suitable. Because everything is unpredictable, haenyeos often express uncertainty, saying ‘We will see, we will wait and see, and we will go and see.’ There is a chance that I may return without meeting them. Even though I don’t mind if my work turns out to be in vain, it would be disappointing if that really happened. But of course, they are not obligated to make time and have a conversation with me.

Wave 3

Even if I manage to meet them in the exhibition space, the awkward atmosphere may prevent us from understanding each other’s language or experiencing the fluidity in our first encounter. Moreover, OO’s life is intricately linked to the lives of the local haenyeos. This relationship is akin to that of “ islands in islands.” I have to be very cautious, since I am the outsider who can just leave and return to the land. I can't let OO, who lives there, handle the emotional aftermath alone. I silently contemplate OO and the haenyeos, feeling powerless to take any action. I feel a sense of emptiness, as if I’ve transformed into a tewak.

I discussed these wavy thoughts with OO before getting on the plane. The opportunity reminded me of my past work with elderly women, but the working conditions of this project are significantly different. It’s a challenging project, but it also comes with anticipation and expectation as we collaborate on figuring out how to make it work. When it comes to elderly participants in the project, their voluntary involvement is the most important factor. If this isn’t addressed before the event, the desires of the organizer or artist could overwhelm the elderly participants. The haenyeos naturally become guarded when they feel that their status and interests are being exploited. Society has long neglected their difficult lives, sick bodies, and marginalization. Suddenly, outsiders have arrived with cameras and microphones and want to capitalize on the haenyeos. Our hope is that we can distance ourselves from this approach. When brainstorming these stories, I found it hard to separate them from OO. The interconnected nature of water means that the lives of haenyeos and OO are already intertwined.

Shall we just see what happens?

Yes, let’s go and wait.

Clouds are drifting past the window. Only disappearing beings remember those who are gone. It is hard to understand why they are still dead while I am still alive here. Ten minutes after takeoff, I’ve been thinking about how the things I lack are like those clouds. I want to believe that the clouds hold everything that have disappeared. I want to believe that an uncertain eternity, whether coming together or falling apart, turns into a cloud. The moments when I had to rely on the assumption that something existed or didn’t exist are travelling with me across the ocean. At the airport, I asked the taxi driver if he could put my bag in the trunk. ‘I can’t lift heavy things...’ he said. I didn’t get to explain that I cannot use my arm well because of a lymph node amputation. The driver got out of the car and quietly put my bag into the trunk. Even when I got off, he did not mind taking out my bag and putting it next to me. He said, “I know it well because my wife used to be sick.” I almost said, “That’s a relief.

“If you don’t go into the water, you’ll die,” one haenyeo says, and another slightly younger haenyeo adds. “If you can’t get out of the water, you will die, too.” While I was in a taxi, I remembered a conversation I overheard from haenyeos on the same boat. I wanted to tell this story to OO, but I completely forgot it while I was too busy counting if it was third time we were seeing each other. OO is a person with whom I feel like I can accomplish anything when I am working with, because of her solubility, like soil and water. Under her guidance, I unpacked my bag and indulged in tot kimbap (translator’s note: a Korean seaweed dish) prepared for me in the house where haenyeo Yihwa Ko used to live. My body flinched when she told me that the haenyeos worked in the sea this morning. I was flustered. ‘Is it wind, or is it water in the air?’ Their fatigue from the sea work was conveyed to me in a mysterious way. “If today doesn’t work, there will be tomorrow,” she said and smiled at me, but the expression on her face was sending a different message. The conductivity of emotions tends to increase near water. Observing her memories and the subtle emotions radiating from her body, I doubted that we would be able to proceed with the project smoothly tomorrow. The short introduction I sent to OO earlier was a jinx.

These salty, wet women may or may not appear. They can come and laugh, or turn away and frown. They can be aggressive or gentle. They may be exhausted, or they may think this means nothing. You cannot invite them for a specific time, location, or purpose. That would be like an attempt to trap water. We can only wait carefully when it splashes again, wondering if words can be water or water can be words

I walked out to the exhibition space, which was near the sea. Even though I couldn’t see it, I could sense the presence of the sea. The air was thick. OO had borrowed the storage space of one haenyeo who usually stores tools and her catch there, and was using it as an exhibition space. I found solace in front of the artworks including OO’s video work, “Why I Swim.” The video was dominated by water and sky blue colors, creating a sense of time slipping away. The exhibition space was filled with the scent of the sea and the sound of the wind, with black stones scattered around. The artworks formed a seamless flow of watery colors, leading from one image to the next, drawing me in. I doubted the haenyeos would come by today, but I felt they were there, just like the sea. I spent the entire night thinking about how to bridge the language gap with those uncomfortable with holding pencils and preparing all kinds of imaginative tools, but I actually did not want them to follow my guidance at all. Surrounded by thoughts of water, one sentence stood out in my mind: ‘We must meet in a place where your voices are loud and clear.’ After a brief conversation, OO and I decided to head toward the community center, where they might be.

Wait a minute: This place is governed by a different order, a body called water.

From the traditional order’s perspective, this place may seem disorderly and messy. Hélène Cixous also wrote a similar sentence about Água Viva. We can reinterpret and rewrite the body in disorder. God belongs to the language of water, but that language does not give God a name. It calls a woman with a body of water only once. Only once. That one time keeps recurring. From a woman to women

Sensing the high humidity of the island, my body kept its pores slightly closed. As I felt that my body was responding accordingly, I opened my ears to the haenyeo’s Jeju dialect. Their bodies seemed to be open but closed as they conversed, being aware of both OO and me. Humidity blurred the boundaries of my body, just three or four hours after my arrival on the island. It would not be at all strange if my body melted quietly among the haenyeos who were seated in a circle. It felt as if I was reliving a dream from the past. Every time the outline of my body vanished in the hospital room, I tried to recall the robust rubber diving suit of the haenyeos, crafted in the most vivid black color I’ve ever seen. I waited for their words to leak or flow toward me, even by mistake, surrounded by the haenyeos without their black diving suits. ‘You have to drink a lot of water. ‘How much?’ ‘Continue drinking, as urination is necessary to drain all the medicine.’ ‘I have to drink a lot of water,’ I wrote in a memo and put it on the refrigerator door. But how much? As much as possible. I had to go through the days of being pushed by the water, going to the bathroom, and dozing off in the bathroom. These were days of overflowing water and insufficient sleep. I felt like I became a water pipe connecting sleep and out of sleep space.

I keep waking up because I have to pee.

It is because you drink too much water before you go to bed.

Two haenyeos sitting next to me were talking about peeing, relating it to a story of water. One of the haenyeos winked at me and asked if I understood. I chuckled and said I only understood a little, and suddenly felt a strong urge to pee. One haenyeo then shared a story about a girl who used to pee in the water during her early years of learning to float and swim with her mother. Even now, in her 50s, the girl dreams of peeing and hiding her wet blankets. ‘Shheee, I am still doing this, even in my dreams.’, she said. I was intrigued by such stories. When my eyes met with OO, I felt a dryness in my mouth. OO told me there were a couple of haenyeos who are opposed to her learning the sea work and becoming a haenyeo. Among them? I peeked at them unsubtly, and they hid their thoughts skillfully. Their lowered gazes and sharp tones made me uncomfortable, as they seemed to be avoiding me. I struggled to keep my ears open and could only catch a few foreign language-like words.

‘Gorangeun molla masseum.’

I later learned that it meant, ‘Words can’t explain this.

I found myself unable to start the conversation I had prepared. As soon as I entered the hall, I forgot everything. After a while, my anxiousness and nervousness slowly faded, and from a certain point I began to feel calm. It gradually dawned on me that of course it should be me , not the haenyeos, who is nervous and intimidated. Even if they were very protective of their community on the island, even if building a wall between insider and outsider, even if I did feel excluded from the circle, their hearts seem to be excited and welcoming the new relations. When they asked me where I came from, as if creating a waterway, rather than pushing me to the edge, I saw it as an opportunity to make a starting point. Water lives inside of water. Words are like water, and I realized I wanted to get closer to the language that lives inside. ‘Words can’t explain this,’ but water can. For a second, I felt like I had gained insight into OO’s thoughts. OO wants to learn about a way of working with bodies of water, while I want to learn the language of body. Whether it’s water or words, we have to be patient. We left the haenyeos from the community center, feeling as if we were navigating the surface of waves and boundaries.

Wait a minute: What is a thing that keeps changing its position without ever being replaced?

On the flight back home, I thought of the answer to the riddle while I was half-asleep and dreaming about being submerged in water. I gazed out of the window and saw the swirling blue hues of the sky or the sea, and the passing clouds. The rippling water transformed into the Medusa of the sky. Clarice Lispector originally envisioned water as turbulent frictions and full of contradictory movements, rather than just flowing smoothly back and forth.

Some time passed. I saw a picture of OO on her social media in a black rubber diving suit, sitting with haenyeos facing the sea. I couldn’t help but let out a quiet exclamation. The image of OO trying to be gentle with her neighbor haenyeo, even though it is still uncomfortable, came and became blurry again. OO resembles two round islands. If the gap between the ‘O’s is removed, it looks like an ‘∞.’ It symbolizes a state of growing larger than the largest imaginable number. When we meet again in the endless water, we will rise to the surface and wash away “the unspeakable things.” We will create bubbling time by moving between two round islands and boundless water. This is what we call a conversation

When words swallow words, over and over again, they eventually become water. When we dive in and our boundaries melt away, shall we start?

* 문화체육관광부와 (재)예술경영지원센터의 지원을 받아 번역되었습니다. Korean-English Translation of this essays is supported by Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism and Korea Arts Management Service'.

-

Ji Yoon (hereafter “JY”)

: Let's start our discussion by sitting inside of the Bulteok. (Translator’s note: This was the title of the installation inside the gallery, and the Korean word bulteok refers to the [1][lH2] Lava rocks of Jeju, where haenyeos, female divers of Jeju Island, change their clothes, take shelter from the wind, and take a break around a campfire). Your solo exhibition, Yo-E Ryou Solo Exhibition: Why I Swim (2023), consists of three sections. The first is a video about your burnout experience in New York. The second section is a textual installation dealing with keywords and personal research about your struggles to rescue yourself, as well as your healing and creative processes. The third video features bulteok, where we are currently seated. It embodies your journey to Jeju, including learning how to swim in the sea, interacting with haenyeo grannies, and learning their way of life. Please introduce your personal experiences, the process of recovery and art practice.

Yo-E (hereafter “YE”)

: It was a question of how I processed many things that were happening in my life at that time. In other words, it was a process of finding a way to understand and solve problems in life. Initially, I didn’t believe that art or feminism could open up different ways to navigate through these issues. While trying various methods to find a way to alleviate my burden, I realized that I needed to first learn how to bring up my story so that I could communicate and start solving my concerns. The act of putting my story out in the world is not easy and requires a lot of courage, but in doing so, I found healing. I think the power of communication is really great, especially when someone listens to and sympathizes with the stories I struggled to share. To me, sharing the story itself is an act of solidarity and one way to live together. The reason for my art practice became clear after I realized that I could connect my stories with myself and beyond if I closely looked into my personal small stories one by one; those stories ingrained in my body, in my family, in our society, even before I was born, rather than just letting go of them.

JY

: At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Loop organized an ecofeminism Zoom workshop that lasted for about 9 months. It was where we met for the first time. The workshop was a learning process for me as well, and I noticed a shift in my perspective before and after I participated. This exhibition also seems to reflect your change in perspective, both before and after your research on ecofeminism. It involves freeing ourselves from the established education and perspective imposed on us by the dominant social system, including the capitalist patriarchy. You refer to it as “unlearning.” I realized that we had been thinking as if a world outside the system didn’t exist. This led to a burnout that made me feel suffocated. Feminism is an alternative to this issue. To begin, shall we start by discussing the backlash and aversion to feminism in South Korea?

YE

: I first encountered feminism in English while studying in the United States in my 20s, so I understood it only in theory. I experienced the freshness and exhilaration of feminism, realizing, ‘Oh, I can see the world from such a perspective!’ I never thought that feminism could be an uncomfortable issue in South Korean society. But during my first lecture in South Korea, a student asked me privately, “Yo-E, are you also a feminist?” That was the moment I realized the harsh social atmosphere towards feminism, which forced this student to whisper and ask questions like that because she was so afraid of being labeled a feminist at school.

: Wondering how to talk about these issues, I wrote a children’s book for gender equality and participated in an ecofeminism workshop. I felt like adding the prefix “eco” seemed to make it a little more accessible and less off-putting.

JY

: I agree. Although ecofeminism is a radical approach within feminism, the ecological perspective makes it more comfortable and less pressured for the public to engage. Ecofeminism is not just a way of thinking, but also a practice in everyday life. In the ecofeminism workshop, I emphasized the importance of challenging the social system beyond personal guilt about ecological issues. This means that, in addition to adopting daily practices such as carrying a tumbler without plastic or using a reusable bag instead of a plastic bag, we also need to critically examine and question the capitalist system. Essentially, that involves discussing the issues of carbon emissions and environmental damage caused by large corporations like the Korea Electric Power Corporation and the Pohang Iron & Steel Company (POSCO), which are considered to be the economic backbone of contemporary Korean society. These questions naturally make everyone uncomfortable.

YE

: Yes, once I became aware of the societal and structural issues, I initially felt overwhelmed. During the ecofeminism workshop, I started weaving together stories of my life in Jeju, my previous experiences, and the special moments I had in the sea, and I was able to connect this with hydrofeminism. In the waters of Jeju, I underwent a profound transformation in my life as well as my body while facing a sense of helplessness with the challenges posed by vast systems. When I started seeing the ecological problem as a social systemic issue, I was finally able to genuinely understand things I had previously only grasped in theory.

JY

: You are currently attending classes at a haenyeo school in Jeju. Through your “Unlearning Space”, you are creating a community space that brings together local haenyeo grandmothers, immigrants, and visitors. You are expanding your artistic activities through hydrofeminism, which examines the relationship between water and body by organizing a reading group, workshops, and exhibitions.

YE

: Yes, that’s right. During the first year after my relocation, I spent a lot of time getting to know the area, environment, and local community. Most of my neighbors are haenyeos, or tourists. I began a community project, such as organizing film screening events, that were open to a wide variety of people. It provided me with the opportunity to connect with locals and other migrants around me. However, our everyday language, perspectives, and ways of life were quite different. I found it challenging to conduct in-depth research in Jeju while ensuring accessibility in the region. That’s why I decided to organize an online book club.

JY

: I’d like to discuss your book club. You started a book club where members read Astrida Neimanis’ Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenon and shared questions online. I wonder if a haenyeo’s body and the sea were one. Did studying hydrofeminism help you better understand the lives of haenyeos?

YE

: As I began to learn how to swim and immerse myself in the bodies of water, I had the opportunity to observe the lives of haenyeo grandmothers up close. As I felt a growing desire to articulate what I experienced, something that seemed intangible in my everyday language, I revisited Astrida's book. I felt like I had found a language that could resonate with the indescribable sensations. The lives of haenyeo grandmothers appeared to perfectly embody the ideas of hydrofeminism. But, since there was no Korean translated version available yet, I had to read the original text, and the fact that it’s rooted in Western philosophical perspectives felt somewhat mismatched. This led me to form a book club to explore and discuss it in our own, non-Western languages.

JY

: You highlighted the importance of “unlearning” which involves deconstructing and dismantling what we already knew from a new perspective. Shall we discuss your concrete experience related to unlearning?

YE

: I often help my 85-year-old neighbor grandmother with small chores as we have become very close. Whether communicating with people from different generations or discussing city life with locals, it’s necessary to be open to unlearning old assumptions.

As I’m currently attending a haenyeo school and learning to dive, I’m also learning to unlearn the way I perceive and sense my body. Humans originally had large and developed lungs, similar to whales and other sea mammals, but their function has deteriorated while living on land. After decades of diving in the sea, a haenyeo’s organs can grow three times bigger and their breathing abilities recover.

: Another reality is that while the haenyeo community is often known as a matriarchal society, most haenyeos had to learn to dive in the sea because they could not afford to go to school. This was how these women earned money and supported their sons' education. The pride in this work is mixed with painful histories and realities.

JY

: I'd like to hear if your view of haenyeo has changed during the process of unlearning. I believe that the shift in perspective on haenyeo is in line with your process of redefining your identity as an artist.

YE

: Initially, I also accepted the symbolic image of the haenyeo and idealized ‘them’ in my vague admiration. But as I built relationships in everyday life, I learned about their heartbreaking stories as daughters working in the sea to support their brothers’ education. On the other hand, I was touched by their resilience as strong women and mothers, and also felt the loneliness of some grandmothers living alone.

: During the winter when they cannot work at sea there’s a pop-up “store” opening for grandmothers who live alone. Every evening, a bus takes the grandmothers there, where they sing for them, and sell a variety of items, such as medicine, red pepper paste, pain relief patches, and more. It’s a place where grandmothers buy things just to spend time with others. At first, I thought it was a kind of illegal pyramid scheme and considered reporting it, but after learning the full story, I started driving grandmothers there myself and just told them to buy only what they needed. I even learned the concept of “nochiewon (senior daycare)” (Translator’s note: a neologism in Korea meaning ‘kindergarten for elders’).

: Through these experiences, I became aware of the competition among the haenyeo, while they need each other to go out to sea, which shows the interdependent yet competitive relationships within the haenyeo community. I also learned about structural conflicts between the haenyeo community and the fish farms. As I learned about the interwoven haenyeo community, I became doubtful about the survival of the traditional haenyeo culture in my generation. I was skeptical and curious about the purpose of running the Haenyeo School. What are they trying to teach? What would be the government’s perspective on haenyeo culture? After a competitive process, I had an interview and got in to the Haenyeo School. It is a learning process about “haenyeo” from the viewpoint of the local government. Although Haenyeo make up 30% of the fishing population on Jeju Island, their income is only about 1%. Despite this, the local government now places cultural and symbolic value on haenyeo, and there is increasing international interest in haenyeo culture, highlighting the role of haenyeos as local cultural products.

: Once you recognize the haenyeo community as an economic collective, it becomes clear that their intention is to strengthen the community to prepare for the era of global warming and the following risk factors. While there's a desire to raise young haenyeo to continue this culture, there's also the reality that if a young haenyeo becomes skilled at diving and catches more, my own income could decrease, leading to tensions. Learning how to float above the surface and now start diving allowed me to see hidden stories below the surface that were previously invisible. This led me to question, ‘So what can I do?’.

JY

: You're planning an exhibition on hydrofeminism at the Unlearning Space. Contemporary art exhibitions may be unfamiliar to haenyeo grandmothers. I wonder how they will perceive the artworks of their lives when the subject of the exhibition is the lives of haenyeos themselves. It might be challenging to discuss hydrofeminism with haenyeo grandmothers, especially considering that a group exhibition is significantly different from making your solo exhibition.

YE

: This is something I’ve been reflecting on lately. I feel a sense of duty to share what I have learned from the sea and the grandmothers. At the same time, I’m concerned that I might be imposing my own perspective on them. They always appreciate it when I print images and give them their pictures, so I’m curious to see how they will react when they watch the video. I am also contemplating how to engage with not only the grandmothers but also their families as well. The audience in Seoul shares a similar language and perspective as mine, but the audience in Jeju may be different. Which factors should I consider?

JY

: When we talk about “community art” in contemporary art, it often involves the creating of fictional communities in local areas. These artists undertake community art projects with funding, and once they leave, the fictional community disbands. Then, another artist starts a similar community art project. Over time, the local residents become tired of participating in these projects. Some locals dislike “community art” because they are repeatedly asked to share their life stories as the subject of art.

If you spend a long time working on art projects in Gujwa-eup, Jeju, it is natural for you to have deep and complex concerns. This is especially challenging considering that the majority of the community consists of haenyeos who are in their 80s.

YE

: I’ve been thinking a lot about that issue while reading Trinh T. Minh-ha’s essay, “Outside In, Inside Out.” How long do I need to stay in a community to earn the right to talk about it? There are things that only insiders, not outsiders, can see.. On the other hand, there are also things that one can no longer see if you are only within the community.

I’ve attended a number of haenyeo performances where the haenyeo directly participate. When haenyeo grandmothers tell the same stories of their lives, the audience laughs and cries at the same point every time. This indicates that haenyeos themselves start creating a tightly organized performance of their narratives.

: I’m currently struggling with an ethical dilemma regarding how much I can use their private stories exclusively shared with me in my artwork. An individual's personal experiences often reflect a broader and more intense political system, as well as the history of a society. I am trying to find a way to address social issues through these personal stories.

JY

: In the exhibition, a small number of participants gathered for a workshop on hydrofeminism and women’s writing, sitting on the bulteok installed in the exhibition. The wall of the exhibition hall featured a drawing installation titled “Water Speaking, Body Writing”, functioning as a kind of map that incorporated concerns and research findings on women’s writing. The aim was to introduce participants to a new approach to women’s writing or speaking within a bulteok setting. A bulteok is a stack of stones along Jeju Island's coast, serving as a community space where haenyeos rest or change their clothes. By creating a bulteok in the exhibition space, you aimed to facilitate workshops to intimately share and discuss personal concerns with the participants.

YE

: Yes, it takes courage to bring one’s concerns out into the open, and a safe and supportive environment with someone listening is also necessary. The concept of women’s writing originated in Western Europe. I found it fascinating to delve into the sensuality of not only writing, but also reading, listening, and speaking. This resonated with me even more because I am in a situation where I had to completely unlearn the language I've been using and learn to use it in a new way.

: Creating a bulteok space in this exhibition was particularly important. I was eager to engage in conversations with others rather than thinking and speaking alone, whether through a hydro-listening workshop or a reading-circle workshop. Hydrofeminism allowed us to recognize that our bodies are connected to a substance called water. It became an important method for participants to understand hydrofeminism by listening to each other, putting their heads together, and speaking from a close distance.

: After organizing exhibitions and programs in the Unlearning Space with participants from the hydrofeminism book club in Jeju, I realized that the exhibition I made at the Alternative Space Loop was my safe space. Apart from practical considerations like installation conditions or location, the most notable difference was the relationship with the audience from Seoul and the participants. Speaking in a space where the audience is prepared to listen creates a comfortable and safe interaction.

: When a local resident visited an exhibition in Gujwa-eup in Jeju, I found that I needed to completely change the way I explained the scope of the exhibition. Even before I could introduce the contents of the exhibition, locals often asked me why I do art, why I need this, and why I do something that doesn’t immediately make money. One local person, who was unfamiliar with contemporary art or exhibitions, even looked for a menu because she thought I had opened a cafe. Because what the grandmothers often encounter in Jeju is mostly tourism businesses, they had a hard time understanding that my art activities were not geared towards making money from tourists.

JY

: How did you usually respond to those types of questions? It is important to explain to the local residents why you are organizing non-profit exhibitions or artistic activities, especially when planning such events related to the community. As an artist, it can be difficult to maintain a critical distance between myself and the community. At the same time, ethical questions arise, such as whether I should integrate as a new member of the community or interact with the community as an artist.

YE

: I explained to them that this was my “work.” For haenyeos, work and labor primarily refer to activities that generate income and fulfill their family's needs. They were concerned about me because I had informed them that I was not yet earning money from this work. I also talked about the responsibility I felt. I told them that I wanted to protect the sea from pollution so that my children could also swim in it and document the incredible work and lives of haenyeo samchuns (Translator’s note: Jeju’s local term for “aunties” or “uncles”). [3][lH4] It became an opportunity for me to ponder fundamental questions such as the role and meaning of art(ist). Starting with personal stories, including what I felt about haenyeo samchuns or what I felt in talking with my mother, I attempted to communicate with water, women, the sea, Jeju's experiences, and relationships.

: After the exhibition at the Alternative Space Loop, as I participated in the Haenyeo School last summer, organized exhibitions and programs in the Unlearning Space, and I also built more relationships with other haenyeos in the neighborhood. Most of my next-door neighbors, whom I assist and stay close to, are in their 80s. I found it easier to communicate about the exhibition with the younger generation of haenyeos. For example, a haenyeo who let me use the storage space , or another lead haenyeo who was appointed oversaw my internship training. They seemed to have a better understanding of my work. Experiencing the generational differences once again, I find it interesting to unlearn and relearn both the language of others and my own.

JY

: However, even the “younger” generation of haenyeos [lH5] aren't exactly young either—they are in their 60s and 70s.

YE

: Actually, even when we talk to someone from our own generation, it can still be difficult to fully understand each other. Even when using different languages, we can still understand each other through gestures, body language and expressions. This experience really opened me up to reflect more on the differences and distances in relationships. Working with people who didn't fully understand what I was doing made me focus more on the “listener.” The way I communicate changes depending on whether I’m monologuing, talking with the elderly women, or addressing an unspecified audience; the choice of words and how the story is conveyed also varies depending on the listener.

: The final step of the Haenyeo School involves joining the fishing village associated with each of our own neighborhood to experience the haenyeo community firsthand and receive mentoring about the characteristics of the sea while practicing. Coincidentally, the leader haenyeo who mentored me happens to be the second daughter-in-law of Yihwa Ko, who used to live in the house where I currently reside in. She has distinct memories of Grandma Ko, whom she took care of until she passed away. She shared that Grandma Ko was a very honorable haenyeo, although perhaps not as a mother. Grandma Ko followed the patriarchal tradition by leaving all her property to her eldest son, which still makes her second son and his wife feel hurt and bitter.

JY

: Instead of creating a community just for the sake of art, you joined a long-existing community where your art evolves as you blend in. You encountered a community whose members are very different from the people you had interacted with before coming to Jeju. There are questions that arise from the process of expanding the ways of communication and understanding the world, as widening your spectrum of understanding different types of people.

YE

: There was an episode from this summer. As part of the Unlearning Space program, we prepared a women's writing workshop to discuss exhibitions with local children, travelers, migrants, and elderly women in my neighborhood. I invited the writer Jiseung Kim, who has spent a lot of time writing and interviewing elderly women. Most of the grandmothers had no prior experience with workshops, and many had never attended school properly, which hindered their ability to write. So, I decided to name the workshop “a time to share the words of water” rather than “to write.”

: “Samchun, we are going to have an art workshop on Friday, September 24th, from 3:00 p.m. to 4:00 p.m. Please come,” I informed them, and marked it on my calendar. But since these elderly women live by a different calendar than mine it was impossible to predict how many of them would show up. As I was spreading the word and preparing, suddenly, each village was given a quota of turban shells that they had to catch to sell at this year's Haenyeo Festival. The day they had to dive for turban shells coincided with the workshop day. Naturally, the art workshop was pushed down the priority list.

: While Jiseung and I were considering whether to postpone the workshop, we decided to change the plan. "Let's just prepare coffee and snacks for the passing haenyeo when they return from work and have a natural conversation." But on the day of the workshop, the wind was so strong that they had to cancel the workday. With the plan constantly changing, that day Ji-seung and I talked about feminine time. Women's time refers to the time when things don’t go as planned and change as a multitude of responsibilities filled up their daily lives—when a child cries, you just have to stop everything and get up. We also talked about haenyeo’s time. Haenyeos move according to the tides and currents, also waiting for the right weather, even if the water conditions are right. Haenyeos operate on a different time frame than we do. This realization led me to reevaluate what it would mean to conduct an art workshop with these elderly women for an hour or two, and to think about the difference between conducting a workshop for my work and for the haenyeos.

JY

: I'm thinking about the concept of “woman's time.” In the overlap of medieval serfdom and modern time, the medieval serf turns into a wage laborer. I've read that there was a lot of physical violence when human life changed from the time of nature to the time of capital. The concept of standard time was invented in the Industrial Revolution, and there was a lot of physical punishment of the worker's body as they learnt to go to the factory by a certain time and work until a certain time. That's how “modern time” became embodied.

The pre-modern and modern periods overlapped at this point. In the absence of the 24-hour concept, haenyeos’ bodily time resembled that of medieval serfs, closely aligning with a pre-modern era. “Why don't you live in modern times?” itself seems to be backwards. In fact, it is we who live in a “changed time,” not them. It was not that long ago that we started living in modern times. There are still many people who live in pre-modern times, like nomads in the Middle East or Mongolia.

: Contemporary art is rooted in Western modernism, which means it often regards pre-modern as something to be studied from an ethnographic perspective. If we want to move away from this approach, what alternative viewpoint could we embrace? In Western Europe, the artist as ethnographer was once treated as if it was an ethical attitude of the artist, and now that that attitude is being criticized again, this leads us to question, ‘what can we do?’

YE

: I am returning to the concept of “unlearning.” I am thinking about that gap when you are trying to live in a modern time and pre-modern time at the same time. It's a process of unlearning the time that your body lives in, and reconnecting with the time that your body lives in. To have a meaningful conversation with someone, I must learn and use their language, because you have to speak the language of the person you're talking to and be in the same flow with them, if you want to really understand what they are saying. But wouldn’t it take at least 10 years to fully embrace another language?

What are your thoughts on incorporating secrets that only people in your community know into your artwork? I am concerned about the potential harm it could cause to the community and those involved.

JY

: You shared the story of Ihwa Ko’s undocumented daughter, and I started thinking about the idea of turning art into fiction. Would it be more inspiring to reimagine the presentation of artworks in exhibitions as fictional stories, rather than taking a purely factual approach? This approach could also allow for the inclusion of non-human elements despite being expressed in human language. It would help address the challenge of revealing the personal narratives of each haenyeo through art, while also giving artists a chance to explore new levels of creativity.

YE

: Yes, as I become more involved in the neighborhood and new things happen every day, there are moments when I’m worried about pointing a camera at my neighbors. I’m pushing the limits of what’s acceptable as I narrate the story, and I’m exploring what my imagination can create through audio alone, without relying on visual images. However, part of me also wants to shed light on the stories, names, and lives of individuals like haenyeos, aunties, and mothers, who have remained unknown and unseen. Ultimately, it is a matter of choosing what kind of story to tell and how to share it.

JY

: You are exploring ways to get involved in the community and assist the haenyeo grandmothers in their daily lives. You have the chance to directly help the haenyeos, but the old community rules may either help or hinder your efforts. How much longer do you plan to stay in Ha do? It is impossible to work there without learning from haenyeos. Have you even started the haenyeo training?

YE

: (Laughs.) I know. If I get to experience and finish my haenyeo training by the end of this year, I'll likely be able to know how long I can stay with the sea and my haenyeo aunties. In fact, some people in my neighborhood oppose the practice of haenyeo internships at the sea. Others argue that even if new haenyeos are allowed to practice, they should wait for several more years before being allowed to join in the community. A new haenyeo joined the neighborhood 15 years ago. I heard that the haenyeo who is worried that I could be too good at diving and that I might take all the catch from them was not accepted by the community for an extended period of time when she first moved here. Most haenyeos were born and raised in this neighborhood or married into this neighborhood.

: There is a local rule that only people who own land or houses in this community can work in the sea. This is the reason they have been holding neighborhood meetings for months regarding me entering the sea. If they don’t accept me, I will just continue to do what I am doing now. If this is the case, the number of local haenyeos will be reduced by half within five years, and that is the reality. Even though they are rejecting my joining the haenyeo community now, I feel like they will gradually accept the changes once we start the training.

: If I choose to stay here longer, I’ll need to find a way to travel back and forth between different time zones. Maintaining a healthy distance is crucial to keep the conversation going between us. I have also started searching for opportunities like residencies, where I can leave Jeju and then return.

: Around this time last year, I was unsure whether I should leave the island and return to the city. Even if I leave someday, I thought I’d like to take the opportunity to tell the story I want to tell. I am grateful to have had a solo exhibition at Loop this year, for attending the Haenyeo School, and for building more relationships in Jeju. The most important thing for me is that I had a lot of fun exhibiting, learning dive into the sea, working, and creating. I want to find a sustainable way to continue make work for a long time.

JY

: I also think that a precarious state is inevitable to artists. It is always a challenging path. What are your plans for next year?

YE

: After the experience of floating only on the surface of the sea, I am planning to create a video or audio essay that now submerges into the sea. I am also working on a performance piece that will be part of the next exhibition, focusing on the relationship between breathing techniques and the human body. I want to organize a breath (숨) orchestra. I will compile my stories and related research in a book format to engage in deeper conversations. I want to share intimate yet collective experiences of water and the body.

* 문화체육관광부와 (재)예술경영지원센터의 지원을 받아 번역되었습니다. Korean-English Translation of this essays is supported by Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism and Korea Arts Management Service'

-

말과 물의 환영(幻影)

“(…) 삶은 이 말할 수 없는 순간이다.

사건 그 자체보다 큰 순간”

-클라리시 리스펙토르, 『아구아 비바』계절답지 않게 춥고 환한 날이다. 방 한가운데에 가방을 활짝 열어두고 무언가를 넣거나 빼기를 반복하고 있다. 지난밤 살해당한 여자의 몸을 운반하던 영화 속 수트케이스가 같은 색이었다는 게 떠올랐지만 한쪽 구석에 무지개 스티커를 붙이는 걸로 충분하다. 바람이 실어 나르는 게 많은 곳이다. 너무 가벼워서는 안 된다. 무거워서도 안 된다. 아주 오래된 것도 새것도 제외다. 클라리시 리스펙토르의 『아구아 비바』가 가방 속으로 들어갔다. 무게를 측정할 수 없는 “살아 있는 물”. 언제나 새것이면서 역사성이 흐르는 물의 순간을 만날 수 있을까. 기대 역시 너무 가볍거나 무겁지 않게.

이름에 ‘ㅇ’을 두 개 가지고 있어서 그는 내 메모에 ㅇㅇ으로 기록되어 있다. 처음 ㅇㅇ의 메일을 받은 날, 나는 병원에서 또 다른 진단명의 가능성을 듣고 추가 검사를 하고 세 시간씩 오후와 저녁 두 번의 강의를 마친 후 늦은 저녁을 먹고 깜빡 잠들어 꿈을 꿨다. 발끝부터 액체에 녹아 몸이 전부 사라지는 꿈이었다. 젖은 소멸에 고통은 없었다. 아드리아마이신, 엔독산주, 탁소텔… 몸을 녹인 액체들의 이름을 나는 알고 있었다. 이름을 알면 아프지 않다. 몸 안으로 들어왔던 그것들이 몸 밖에서 몸을 녹였다. 안팎의 전환에 어떤 기억이 창백해졌다. 액체가 꿈틀거렸다. 녹아 사라진 줄 알았던 몸이 그 속에서 젤리처럼 투명하게 형태를 유지하고 있었다. 저건 내가 아니다, 거듭 확신하며 꿈에서 나왔다. ㅇㅇ이 보낸 ‘섬 안의 섬’으로의 초대 메일 속 글자들이 물방울처럼 침대 위로 뚝뚝 떨어졌다. 아무것도 하고 싶지 않았다. 동시에 무언가를 해야 한다는 걸 알았다. 가령, 자기 경험을 해석하기 위해서 다른 여성의 경험에 의지해야 한다든가. ㅇㅇ에게 답장을 썼다. 초대 고맙습니다.

아직 가져갈 것을 다 결정하지 못했다. 가방이 자기 몸을 활짝 열고 시간을 삼켰다 뱉어냈다. 시간이 흘렀다, 라고 써도 될텐데 쓰고 나면 정말 그런가 시계를 보면서도 의심하곤 한다. 시간이 균일한 방향성을 가지고 일정하게 운동하고 있다는 걸 매번 믿기 어렵다. 틈입하거나 절룩거리거나 잠기는 시간이 아니고, 누출되거나 미혹되는 시간도 아니고, 0에서 9까지 타고 흐르는 시간에 관해서 나는 잘 모른다. 유아가 시간을 측정할 수 있으려면 좌절을 견딜 수 있어야 한다고 K 교수가 말했을 때 나는 그 말의 의미를 단박에 이해했다. 말하자면 생애 첫 대상인 엄마의 가슴이 자기 곁에 있을 때와 부재할 때의 간격으로 우리는 처음 시간을 인식한다. 첫 대상이 오고 가는 사이, 부재로 느끼는 좌절의 감각이 곧 시간일지 모른다. 몇 년 전 만난 부산 영도 해녀들 중 상군 해녀 하나가 “물이 오고감이 물때”라고 해삼을 탁, 소리나게 반토막내며 말했던 게 떠올랐다. 오고 가는 사이, 파도가 평평해지는 순간, 들숨과 날숨이 교차되는 찰나 우리가 느끼는 시간은 그런 것이다. 이번에 내가 만나야 할 사람들은 ㅇㅇ가 살고 있는 제주 한 바닷가 마을의 해녀들이었다. 물의 시간을 살며 멀리 갔다 온 언어를 쓰는 사람들. 떠올리는 것만으로 마음이 출렁거렸다. 엘렌 식수의 『제3의 몸』을 마지막으로 넣고 수트케이스를 닫았다. 이 가방이 불능의 몸을 운반할 것이다. 섬까지 내 몸을 운반하는 문제 외의 문제들은 섬에 있었다. 내가 가는 것인데 그들이 오는 것 같다. 비행기 안에서 곧 내게 밀려올 것들을 적는다. 그것들을 파도라 하자.

파도 1.

그동안 공공 기관과 협업해 진행한 프로젝트는 주관하는 곳에서 주로 모객부터 행사 전반을 세팅하고 내 역할이 주어졌다. 그와 달리 이번 프로젝트는 해녀들의 참여 여부 자체가 공적 약속으로 묶기 어려웠다. 그들을 움직이는 건 물때다. 대화 장소로 그들을 오게 하고, 한두 시간 몸과 마음을 붙잡아 두는 게 과연 가능할 것인가. 나는 물이 아니다(굴, 술, 줄도 아니지)파도 2.

제주해녀축제를 앞두고 부스에서 판매할 해산물을 채집하기 위한 물질이 예정되어 있다고 했다. 날씨와 물때가 맞아야 가능한 물질이지만 날씨도 물때도 예측할 수 없으니 결국 그들의 약속은 그때 보고, 두고 보고, 가서 보고 식이다. 어쩌면 그들과 마주앉아 보지도 못하고 돌아와야 할지 모른다. 헛걸음을 좋아하는 편이어도 정말 그렇게 되면 아쉬울 것 같다. 그들에게 맡겨놓은 말이 있는 것도 아닌데.파도 3.

불편한 기류를 감수하고 어찌어찌 그들과 전시 공간에서 만난다고 해도 첫 만남에 서로의 언어에 선뜻 매달리거나 언어의 유동성을 경험하지는 못할 터였다. 더구나 ㅇㅇ와 해녀들의 삶은 연결되어 있다. “섬 속의 섬”이라는 관계. 육지로 돌아오면 그만인 섬 밖의 사람인 나는 조심하는 마음이 계속 커진다. 감정의 여파를 그곳에 사는 ㅇㅇ이 혼자 감당하게 할 수는 없다. 이러지도 저러지도 못하는, 좀체 자리가 잡히지 않는 마음으로 은밀하게 나는 ㅇㅇ와 그들을 생각한다. 몸이 텅 비면서 꼭 태왁이 된 것 같다.비행기를 타기 전 ㅇㅇ와 이런 걱정을 공유했다. 그간 진행해 온 여성노인들과의 여러 작업들을 염두에 둔 초대였으나 이전 작업 조건과는 사뭇 달라 난감하면서도 이런저런 궁리를 함께하며 약간의 기대와 흥분이 더해지기도 했다. 프로젝트에 노인 참여자들을 고려할 경우 무엇보다 그들의 자의적이고 창발적인 참여가 중요하다. 그런 면이 전제되지 않으면 자칫 기획자나 아티스트의 욕망에 그들을 교묘하게 동원하는 게 된다. 자신들을 향한, 부쩍 달라진 호명의 빈도와 구획되는 의미를 막연하게나마 직감한 해녀들이 외부인에게 경계심을 높이는 건 자연스러운 반응이었다. 팍팍한 생계에, 아픈 몸에, 소외에 관심이 없던 세상이 갑자기 그들을 향해 카메라와 마이크를 앞장 세워 자본이 되어 달라 요구하는 형국이었다. 그러니 적어도 그런 접근과는 달라야겠다 했다. 어느 순간부터 그들과 ㅇㅇ이 잘 분리되지 않았다. 물이 물을 껴안는 것처럼 해녀들의 삶은 이미 ㅇㅇ의 삶이기도 했다.

그냥 어떻게 되는지 볼까요?

그래요. 가서 기다려보죠.

창밖으로 구름이 지나고 있다. 사라지고 있는 존재만이 사라진 존재를 기억한다. 내가 여전히 살아 있는 게 이상하게 느껴지는 순간마다 그들이 여전히 죽어 있는 게 이해되지 않는다. 나에게 결여된 것들이 저 구름 같다는 생각을 이륙하고 10분이 지나고부터 하고 있다. 사라진 것들은 다 어디로 가나 할 때 저기 있다고 믿고 싶다는 생각. 확신 없는 영원성을 뭉치거나 풀어헤치면 구름이겠거니 하는 생각. 그러니까 무언가 어딘가 있다 치고, 없다 치고 살지 않으면 안 된다 했던 순간들이 함께 바다를 건너고 있었다. 공항에서 택시기사에게 가방을 트렁크에 좀 실어줄 수 있냐고 물었다. 제가 무거운 걸 못 들어서… 림프절 절단으로 팔을 잘 못 쓴다고 설명할 여유는 없었다. 기사는 차에서 내려 묵묵히 트렁크에 가방을 실었다. 내릴 때도 귀찮은 내색 없이 가방을 꺼내 내 가까이 놓아주며 말했다. 집사람이 아파봐서 잘 알아요. 무심코 다행이네요, 라고 할 뻔했다.

물에 들어가지 않으면 죽어, 라고 한 해녀가 말했다. 옆에서 다른 젊은 해녀가 중얼거렸다. 물에서 못 나와도 죽지. ㅇㅇ에게 이 짧은 대화를 전하고 싶었다. 세 번째인가. ㅇㅇ는 무엇이든 같이 도모할 수 있겠다 싶은, 개방성의 이미지가 강한 사람이다. 그가 안내하는 대로 고이화 해녀의 생가였던 곳에 짐을 풀고 준비해준 톳김밥을 먹었다. 오전에 해녀들이 물질을 했다는 말에 내 몸이 발끝부터 반응했다. 당황스러웠다. 바람일까, 공기 중의 물일까. 그들의 피로감이 알 수 없는 경로를 통해 내게 전달되었다. 오늘 안 되면 내일도 있으니까요. 말은 그렇게 하고 서로 웃었지만 가까이에서 느껴지는 ㅇㅇ 몸의 표정은 다른 메시지를 전하고 있었다. 물 가까이에서는 감정의 전도율이 높아진다. 미미하게 발산되는 몸의 기억, 감정을 읽자니 내일도 수월하게 진행될 것 같진 않았다. ㅇㅇ에게 보낸 짧은 소개글이 예언이 된 것 같았다.

이 짜고 축축한 여성들은 올 수도 있고 안 올 수도 있다. 와서 웃을 수도 있고, 돌아서며 찡그릴 수도 있다. 과격하거나 잔잔할 수도 있다. 지쳤을 수도, 아무 의미가 없다고 여길 수도 있다. 정확한 시간, 장소, 의도에 그들은 초대되지 않는다. 그건 마치 물을 가두려는 시도. 다만 조심조심 찰랑이며 기다릴 것이다. 말이 물이 되거나 물이 말이 될 수 있을까 하며.

바다 가까이에 있다는 전시 공간으로 나갔다. 바다가 보이지 않아도 거기 그냥 있다는 걸 알 수 있었다. 기척이 진하다. ㅇㅇ는 평소 물질 도구를 보관하는 한 해녀의 창고를 금채기에 빌려 전시 공간으로 사용 중이었다. 궁금했던 작가들의 작품과 ㅇㅇ의 영상 작업, <내가 헤엄치는 이유> 앞에서 잠깐 걱정을 잊었다. 영상에는 물색과 하늘색이 가득했다. 그 앞에서 누출되는 시간을 느꼈다. 전시 공간의 검은 돌 주변으로 바람과 냄새가 들락거렸다. 하나의 이미지가 다른 이미지로 이어지고, 서로가 서로에게 관여하는 방식으로 전시장의 작품들은 물빛의 연속체를 이루고 있었다. 그들은 오지 않을 모양이었다. 바다처럼 그들도 저기 어딘가 있을 것이다. 손에 연필을 쥐는 일 자체가 어색하고 불편한 이들의 언어와 연결해 볼 다양한 상상적 도구들을 고심하고 밤새워 준비해왔으면서도 어쩐지 나는 그들이 이곳에 와서 내가 기획하고 가리키는 방향으로 움직이는 걸 정말 원하지는 않고 있었다. 물빛 연속체에 둘러싸여 있자니 알 것 같았다. 마음에서 한 문장이 부풀었다. 당신들의 목소리가 크고 카랑한 곳에서 만나야 한다. ㅇㅇ와 나는 (그들이 있을지도 모르는) 마을회관으로 향했다.

잠깐: 다른 질서가 지배하고 있다. 물이라는 몸.

고전적 질서의 관점에서 보면 무질서하다고도 할 수 있다. 『아구아 비바』에 대해 엘렌 식수가 쓴 문장도 비슷하다. 우리는 그 몸을 다시 무질서하게 쓸 수 있다. 신은 물의 언어에 속하지만 그 언어는 신에게 이름을 주지 않는다. 오직 물의 몸을 가진 여자를 단 한 번 부른다. 한 번만. 그 한 번이 계속 돌아온다. 여자에서 여자들로.

섬의 높은 습도를 느끼며 몸의 구멍들을 조금 닫아둔다. 그렇게 하고 있다고 느끼면서 진짜로 하는 일은 해녀들의 제주 방언에 귀 기울이기. ㅇㅇ와 나를 연신 의식하면서 자기들끼리만 말을 주고받는 그들의 몸은 열린 듯 닫혀있다. 섬에 도착한 지 고작 서너 시간, 습기 때문에 몸의 경계가 흐물흐물해진다. 둥그렇게 둘러앉은 해녀들 틈에서 조용히 녹아내려도 이상할 게 없겠다. 그때 그 꿈처럼. 병실에서 몸의 윤곽이 지워지려 할 때마다 내가 아는 가장 생생한 검은색으로 만들어진 해녀의 고무옷을 떠올리곤 했다. 검은 옷을 벗은 해녀들 사이에서 실수로라도 말이 내 쪽으로 새거나 흐를까 기다린다. 물을 많이 마셔야 해요. 얼마나요? 약이 소변으로 다 빠져야 하니까 계속 마시도록 하세요. 나는 물을 아주 많이 마셔야 한다, 라고 냉장고 문에 써뒀다. 하지만 얼마나 많이? 가능한 많이. 물에 떠밀려 화장실에 가고, 화장실에서 졸고, 물은 넘치고 잠은 모자라는 날들이 계속되었다. 잠과 잠 밖을 잇는 길이 수관(水管)이 된 것 같았다.

오줌이 자꾸 마려워 잠을 깨.

자기 전에 물을 많이 마시니까 그렇지.

내 옆에 앉은 해녀와 그 옆의 해녀도 오줌 이야기를 한다. 물 이야기이기도 하다. 무슨 말인지 알아듣겠냐고, 옆 해녀가 눈짓을 한다. 대충 알아들었어요, 하고 웃자니 갑자기 오줌이 마려웠다. 걸음마를 떼고부터 엄마 따라 바다에 들어가서 떠 있다가 가라앉다가 조급히 나아가려 했던 한 소녀는 물속에서 소변을 보는 버릇이 이불까지 따라왔다고 했다. 50대가 된 소녀는 지금도 종종 꿈에서 오줌을 싸고 이불을 숨긴다고 했다. 쉬- 꿈에서도 입으로 그러고 있어. 그런 이야기를 하고 싶다. ㅇㅇ와 눈이 마주치자 입이 마른다. ㅇㅇ가 물질을 배우고 해녀가 되려는 걸 반대하는 이들이 있다고 했다. 저들 중에? 나는 서툴게 살피고 그들은 노련하게 감춘다. 경계심을 낮게 깔아둔 시선과 나를 피해 서로에게만 닿는 꼬장꼬장한 말투에 몸이 밀리고 눌린다. 귀만 겨우 열어놓고 있다. 외국어나 다름없는 문장 속에서 짧은 하나를 건져 올린다.

고랑은 몰라 마씀.

의미는 나중에야 도착한다. 말로 해서는 몰라.

준비해온 대화는 시작조차 하지 못했다. 회관에 들어서는 순간 다 잊어버렸다. 얼마간 초조하던 마음이, 쩔쩔매던 두 손이 어느 시점부터는 평온해졌다. 서서히 그런 생각도 들었다. 초조하고 쩔쩔매는 이는 늙은 해녀들이 아니라 나여야 한다. 그들이 경계심을 쉽게 풀어주지 않아서, 섬과 섬밖의 이들을 차갑게 구분해서, ‘우리’에 나는 없어서 몸을 조심히 물리면서도 뒤따라오는 새로운 관계적 상상과 몸의 위치가 반가웠으니 마음은 물리지 않은 셈이다. 좀체 여지를 주지 않던 그들이 그래도 막다른 곳으로 몰지는 않고 물길 하나 열어주듯 내게 어디에서 왔냐 묻던 그 순간을 시작점으로 삼기로 했다. 물 안에 물이 있는 것처럼 말 안에 말이 산다. 다음에는 그 안에 사는 말에 조금 더 가까워지고 싶다. 말로 해서는 모릅니다. 그러니까 말 말고 물로. 잠시 ㅇㅇ의 마음에 닿은 듯한 착각이 들었다. 물질을 배우고 싶어하는 ㅇㅇ. 몸의 말을 배우고 싶어하는 나. 물이든 말이든 기다려야 한다. 우리는 어떤 외면과 경계로 출렁거리는 해녀들의 회관에서 정중하게 물러났다.

잠깐: 결코 대체되지 않으면서 계속 자리를 바꾸는 것은?

몸이 물에 녹는 꿈속에서 받은 질문의 답을 돌아가는 비행기에서 떠올렸다. 창밖으로 하늘의 것인지 바다의 것인지 모를 파란색이 펼쳐지고 구름이 흐른다. 저 부푼 물의 변신, 하늘의 메두사. 클라리시 리스펙토르가 처음 생각했던 물은 부드럽게 오고가는 물이 아니라 거품이 생명처럼 부글거리는, 마찰과 모순적인 운동으로 살아있는 물이었다.

얼마 후 ㅇㅇ의 SNS에서 그가 검은 고무옷을 입고 해녀들과 바다를 향해 앉아 있는 사진을 봤다. 나도 모르게 낮은 탄성이 샜다. 여전히 얼마간은 불편한 채로 그들의 마음을 살피며 함부로 어떤 때를 결정하지 않으려 애쓰는 ㅇㅇ가 그려지다가 흐릿해졌다. ㅇㅇ는 동그란 두 섬을 닮았다. 거리를 두지 않으면 ㅇㅇ 가 된다. 생각할 수 있는 가장 큰 수보다 더 커지고 있는 상태. 우리가 무한대의 물로 다시 만나면 “말할 수 없는 것들”을 거품이 나도록 씻어낼 것이다. 두 개의 동그란 섬과 무한대의 물을 오가며 부글거리는 시간을 창조하는 것. 그러니까 우리에게 대화란.

말이 계속 계속 커지면 물이 돼요. 거기 몸을 담그고 경계가 녹는 순간에 우리 시작해볼까요?

-

Ji Yoon

오붓하게 불턱에 앉아 시작할게요. <요이 개인전>은 세 파트로 구성되어 있어요. 일층은 작가가 뉴욕에서 겪었던 번아웃에 관한 경험을 담은 영상작업이 있고요. 두번째는 스스로 구출하기 위해서 분투를 시작하고, 본인의 치유와 창작 과정에서의 키워드, 리서치에 대한 텍스트 설치 작업입니다. 세번째는 저희 앉아있는 불턱을 포함한 영상 작업으로, 제주로 이주를 하면서 바다수영을 배우고 해녀 할머니들과 교류를 하면서 그들의 삶의 방식을 배우면서 작업이에요. 작가의 개인적인 경험, 치유의 과정, 예술 창작의 과정에 대해 소개해주시면 좋을 것 같아요.Yo-E

여러가지 제 삶에서 일어나는 일들을 어떻게 소화하느냐의 문제였어요. 삶에서의 문제를 이해하고 풀어가는 방법을 찾는 과정이었어요. 처음에는 예술이, 페미니즘이 그 방법이 될 수 있다는 것을 몰랐던 것 같아요. 다양한 방법으로 일을 하기도 하고, 치유의 방법을 찾기도 하다가, 어느 순간에 내 이야기를 꺼낼 줄 알아야 내가 고민하는 것을 소통할 수 있고 풀어나갈 수 있겠구나 라는 생각이 들었어요. 이야기를 밖으로 꺼내는 행위 자체가 쉽지 않고 큰 용기를 필요로 하지만, 내 이야기를 꺼내는 것 자체에서 치유를 받는 것, 그리고 그렇게 어렵게 내가 꺼낸 이야기를 듣는 사람이 존재하고 그가 공감을 했을 때 이루어지는 소통의 힘은 대단한 것 같아요. 이야기를 꺼내는 것 자체가 연대이고 함께 살아갈 수 있는 방법 중에 하나가 아닐까 라는 생각이 들었어요. 저의 작은 사적인 이야기들, 어쩌면 제가 태어나기 이전부터 내 몸에, 내 가족들에게, 우리 사회에, 배어있는 이야기들을 그냥 흘려보내는 것이 아니라 하나씩 들여다보았을 때 제 자신과도 연결될 수 있고, 더 큰 세계와 연결될 수 있다는 점을 인지하고 나니까 창작의 이유가 분명해진 것 같아요.JY

코로나 초기에 9개월 정도 루프에서 에코 페미니즘 워크숍을 줌으로 진행했어요. 그때 저희는 처음 만났어요. 워크샵은 제 스스로에게도 깨달음의 과정이었고, 그 워크숍을 참여하기 전과 후의 제 관점의 변화를 느껴요. 이 전시에서도 작가가 에코페미니즘에 관한 리서치를 하기 전과 후가 나타나는 것 같아요. 이는 사회 주류 시스템인 자본주의 가부장제가 만들어낸 우리들 몸에 배어있는 교육과 관점을 벗어나는 과정인 것 같아요. 요이 작가는 언러닝이라고 표현하구요. 시스템 외부의 세상은 존재하지 않는 것 처럼 생각하고 있었다는 것을 깨달았어요. 이 때문에 질식할 것 같은 번아웃이 오기도 하구요.그 대안으로서의 관점을 페미니즘이라고 볼 수 있는데요. 우선 한국에서는 페미니즘에 대한 혐오나 반감이 있다는 현상 부터 이야기를 시작해볼까요? 부담스럽고 꺼리게 되는 경향이 있기 때문에, 줌을 통해 이야기 나누는 것이 편하기도 했어요.

YE

20대 미국에서 공부하면서 페미니즘을 영문으로 처음 접했기 때문에, 사실 머리로만 이해했던 것 같아요. ‘오, 이런 관점에서 세계를 볼 수 있네’라는 신선함과 통쾌함을 경험했어요.한국 사회에서처럼 페미니즘이 불편한 이슈가 된다는 것을 피부로 느끼지는 못했어요. 하지만 한국에서 처음 강의를 할 때, 한 학생이 ‘요이도 페미니스트에요?’라는 질문을 아주 조심스럽게 개인적으로 물어봤어요. 학교에서 페미니스트라고 분류되는 것이 두려워서 이 학생은 그렇게 속삭이며 질문할 수 밖에 없었던 사회 환경을 알게 되었죠.

이런 이야기를 어떻게 나눌 수 있을까 고민하면서, 어린이를 위한 성평등 동화책을 만들고 에코 페미니즘 워크숍도 참여했요. ‘에코’ 페미니즘이라 부르니, 조금 접근성이 넓어지고 거부감이 줄어드는 느낌을 받았어요.

JY

맞아요. 사실 에코 페미니즘은 페미니즘 중에서도 급진적인 접근이지만, 생태적 관점이라는 접근법 때문에 시민들이 좀더 편히 다가올 수 있더라구요. 에코 페미니즘은 하나의 사고 체계이면서도 일상에서 실천이 중요한 문제인데요. 에코 페미니즘 워크샵을 진행하면서 생태 문제에 관한 개인적 죄책감에서 벗어서 사회 시스템을 고민해야 한다는 점이 중요했어요. 플라스틱을 안쓰고 텀블러를 가지고 다니기, 비닐 봉지 대신 에코백을 들기 같은 일상의 실천과 동시에, 자본주의 체제에 대한 질문이 필요했어요. 지금의 한국사회를 경제적으로 지탱하는 사업들, 한국전력, 포항제철 같은 대기업이 만들어내는 탄소와 환경 파괴 문제를 어떻게 바라보고 이야기해야 하는지에 관해서요. 이런 질문은 모두를 불편하게 만들지만요.GUEST 1

이 전시를 보고 이야기를 들으면서, 에코페미니즘이라는 제가 잘 모르는 개념도 개인적 서사로 풀어내었을 때 잘 공감할 수 있는 지점이 있었어요.YE

네 저도 사회적인 문제, 구조적인 문제를 인지하고 나니 처음에는 막막함을 느꼈어요. 에코페미니즘 워크숍을 통해 제주에서의 제 삶, 그 이전 삶의 이야기, 바다에서의 경험한 특별한 순간을 연결하니 에코페미니즘 안에서도 하이드로 페미니즘이라는 또다른 접점을 찾게 되었어요. 거대한 체제의 문제에서 느끼는 무기력함과 동시에, 제주의 물 안에서 제 삶의 변화, 제 몸의 변화를 경험했어요. 다시 돌아가 생태 문제를 사회 체제의 문제를 바라보게 되니 처음 머리로만 이해했던 것들을 몸으로 이해할 수 있었어요.JY

요이 작가는 현재 해녀학교에서 수업을 듣고 있어요. 제주에서 언러닝 스페이스을 통해 이웃 해녀 할머니와의 커뮤니티 공간을 만들어 가고 있는데요. 물과 몸의 관계를 연구하는 하이드로 페미니즘을 통해 예술 활동으로 확장을 시도하고 있어요. 리딩 그룹도 만들고 워크샵, 전시도 만들면서요.YE

네, 맞아요. 그런데 처음 일년은 제가 위치하고 있는 지역과 환경, 커뮤니티를 이해하는데 더 많은 시간을 보낸 것 같아요. 제 이웃이 해녀 할머니와 여행객이기에, 영화 상영 같이 다양한 사람들에게 열려 있는 커뮤니티 프로젝트로 시작했어요. 이웃 할머니를 초대드려 이야기를 나누고, 주변 이주민과 소통할 수 있는 계기가 되었어요. 하지만 서로가 사용하는 언어나 관점, 삶의 방식이 많이 달랐어요. 지역에서 접근성을 확보하며 깊이 있는 연구를 하기는 어렵다고 느꼈기에, 온라인으로 북클럽을 진행했어요.JY

북클럽 이야기를 할까요? 아스트리다 니마니스의 책 <Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenon>을 읽고, 온라인 상에서 질문을 공유하는 방식으로 진행했어요. 해녀 할머니의 몸과 바다는 하나이지 않을까라는 생각이 들어요. 하이드로 페미니즘에 대한 공부가 해녀 할머니의 삶을 이해하는 데 도움이 되었을까요.YE

JY

작가는 ‘언러닝’이라는 개념이 중요하다고 말했죠. 기존에 알고 있는 것을 무너뜨리고 새로운 관점에서 탈-배움을 실천하는 것이에요. 언러닝에 대한 구체적인 경험을 이야기해 볼까요?YE

가깝게 지내며 자주 도와드리는 옆집 할머니는 85세예요. 완전히 다른 세대와 이야기할 때에나, 지역에서 살면서 도시의 삶과 소통하는 데 언러닝이 필요해요.지금 해녀학교를 다니면서 잠수를 배우는 과정에서 몸을 감각하는 방식에 대해 언러닝하는 법을 배우고 있어요. 원래 인간도 고래나 포유류처럼 크고 발달된 폐가 있었는데, 육지에 살면서 폐의 기능이 퇴화된 것이라고 해요. 잠수를 수십 년 한 해녀는 (콩팥) 장기가 3배씩 더 커지기도 하고 호흡 능력도 회복되고요.

또다른 현실은 해녀 사회가 겉으로는 모계 사회라고 말하지만, 대부분의 해녀는 학교갈 형편이 안 되어서 바다에서 물질을 배웠던 거죠. 그렇게 번 돈으로 아들들 공부시키고. 자랑스럽게 생각하는 마음에는 마음 아픈 역사와 현실이 있어요.

JY

언러닝의 과정에서 해녀를 보는 관점이 바뀌었는지 듣고 싶어요. 해녀 할머니를 바라보는 관점의 변화는 요이 작가가 제 정체성을 새롭게 만드는 과정과 맞닿아 있어요.YE

처음에는 저도 상징적인 해녀의 이미지를 당연하게 수용하고, ‘그들’을 바라보며 막연히 동경하는 마음을 가졌던 것 같아요. 일상에서 관계를 맺어가면서, 아들 교육을 위해 딸은 물질을 해야 했던 마음 아픈 현실을 알게 되었어요. 한편 내면에는 강인한 여성, 엄마로 생활을 이어가는 모습에 감동하기도 하고요. 혼자 지내는 할머니의 외로움도 느낄 수 있었어요.겨울에 물질을 많이 안 나갈 때 혼자 사시는 할머니들 대상으로 반짝 ‘가게’가 생겨요. 매일 저녁 할머니를 버스로 모셔다가 노래 불러 드리고, 약도 팔고, 고추장도 팔고, 파스도 파는 거예요. 사람들과 어울려 시간을 보내고 싶은 마음에 할머니가 이것 저것 사는 곳이었어요. 처음에는 다단계 불법 행위 같아서 신고하려다, 그 속사정을 알게 되니 할머니를 차로 태워 드리기도 하고, 적당히 사라고 말하게 되더라구요. ‘노치원’이라는 개념도 알게되었어요.

할머니끼리의 경쟁, 서로가 있어야 바다에 나갈 수 있으니 서로가 필요한 관계. 해녀 커뮤니티와 양식장과의 구조적 갈등 같은 실질적인 문제를 알게되었어요. 촘촘히 구성된 해녀공동체에 대해 알게 될 수록, 제 세대가 전통적 의미의 해녀 문화를 이어가는 것은 어렵고 결국 사라지게 될 것을 확신했어요. 해녀 학교에 대해서도 회의적이었는데, 또 궁금해지더라고요. 뭘 가르치려고 하는 걸까? 정부 기관에서는 해녀 문화의 어떤 점을 중요하다고 느끼는 것일까? 결국 면접도 보고 나름 경쟁을 뚫고 해녀학교에 입학해서 다니고 있는데요. 지자체의 관점에서 ‘해녀’라는 존재를 배우는 과정이예요. 해녀는 어업 인구의 30%이지만 실질적 경제적 소득은 1%정도밖에 안된다고 해요. 하지만 국제적으로 해녀에 대한 관심이 높아지면서, 그 문화적/상징적 가치 때문에 지자체에서 문화 상품처럼 이어가는 역할이 더 커지고 있어요.

해녀 공동체를 경제 공동체로 인지하고 나면, 지구 온난화 시대를 대비하기 위해 공동체의 결속력을 다져야 위험 요소를 줄일 수 있다는 생각이 이해되지요. 애기 해녀를 키워서 이 문화를 이어가자는 마음이 들다가도, 애기 해녀가 잠수를 잘해서 많이 잡아가면 제 수익이 줄기에 내쫓기도 하구요. 이제 막 수면 위로 뜨는 법을 배웠다면 잠수를 시작하면서 이전에는 볼 수 없는 수면 아래의 이야기가 하나씩 보이기 시작해요. 그래서 내가 무엇을 할 수 있을까? 라는 질문이 들어요.

JY

언러닝스페이스에서 해녀에 관한 전시를 기획 중이죠. 현대 미술 전시라는 형식은 해녀 할머니에게 낯설고, 전시의 주제가 해녀의 삶이라면 해녀 할머니가 제 삶에 관한 전시를 관객으로서 어떻게 볼지 궁금해요. 하이드로 페미니즘을 해녀 할머니에게 이야기하기란 쉽지 않고, 요이 작가의 개인 작업과 기획전은 또 다르기도 하구요.YE

계속 고민하고 있는 지점이예요. 바다로부터, 할머니로부터 제가 배운 것을 공유해야 한다는 의무감을 갖고 있고, 한편으로 내 사고방식을 강요하는 것은 아닌가 하는 의문이 들어요. 제가 촬영한 사진을 인화해서 드리면 정말 좋아하시거든요. 영상을 보면 어떤 반응일지 궁금해요. 할머니 뿐만 아니라 할머니의 가족분과 나누는 방법을 고민하고 있어요. 서울 전시의 관객은 저와 비슷한 지점에서 비슷한 언어를 쓴다면, 제주 전시의 관객은 다를 수 있다고 생각해요. 어떤 것을 고려해야 할까요?JY

현대미술에서 커뮤니티 아트라고 한다면, 예술가가 어떤 지역에서 가상의 커뮤니티를 만들기도 하죠. 기금을 받아서 커뮤니티 아트를 진행하고 예술가가 떠나면 가상의 커뮤니티는 해체되구요. 또 다른 예술가가 와서 비슷한 커뮤니티 아트를 반복하면 정작 지역민들은 참여 피로도가 쌓인다고 해요. 제 삶의 이야기를 예술의 소재로 제공하기를 반복해야 하는 상황 때문에 ‘커뮤니티 아트’를 싫어하는 시민들이 생기기도 하죠.요이 작가가 오랜 시간을 제주 구좌에서 지내며 예술 작업을 진행한다고 하면, 또다른 깊이의 고민이 생기는 것이 당연한 것 같아요. 여든이 넘은 해녀가 대부분의 커뮤니티 일원인 경우 더 쉽지 않은 것 같아요.

YE

트린 티 민하 의 에세이, <아웃사이드 인, 인사이드 아웃>을 읽으면서 그 고민을 많이 했어요. 얼마나 그 커뮤니티에 들어가야 커뮤니티에 관해 말할 자격이 생기는 것일까요? 내부에 들어가야만 볼 수 있는, 외부에 있는 사람들이 절대 볼 수 없는 것들이 있어요. 한편 그 공동체 내부에만 있으면 볼 수 없는 것, 더이상 보이지 않는 것들이 있어요.해녀가 직접 참여하는 공연에 여러 번 갔어요. 할머니가 제 삶의 이야기를 매번 똑같이 들려주면, 관객들은 매번 똑같은 지점에서 웃고 울어요. 해녀 스스로가 가상의 내러티브를 만들어 빼곡히 짜여진 퍼포먼스를 반복하는 거죠.

한편 내게만 해준 사적 이야기를 제 예술 작업 안에서 얼마나 담아도 되는지에 대한 윤리적 질문이 있어요. 한 개인의 사적 경험은 생각보다 훨씬 광범위하면서도 촘촘한 정치 제도와 한국사를 반영하고 있어요. 사적인 이야기를 통해 사회 체제적인 이야기를 할 수 있는 방법을 찾고 있어요.

JY

소수의 참여자가 전시장에 설치한 불턱에 앉아 하이드로 페미니즘과 여성적 글쓰기 워크숍을 진행했어요. 전시장 벽에 <Water Speaking, Body Writing>이라는 드로잉 설치 작업을 만들었는데, 여성적 글쓰기에 관한 작가의 고민과 리서치를 담은 일종의 맵map이었어요. 여성적 글쓰기, 혹은 여성적 말하기의 새로운 방식을 불턱 공간에서 참여자와 나누는 것이죠. 불턱은 제주도 해안가에 돌을 쌓아 해녀들이 휴식을 취하거나 옷을 갈아입는 커뮤니티 공간이죠. 전시공간에 불턱을 만들어 참여자와 함께 제 고민을 밖으로 꺼내어 표현해 보는 워크샵이었어요.YE

네, 고민을 밖으로 꺼내는 데에는 용기가 필요하고, 들어줄 사람이 있는 안전한 공간도 필요해요. 여성적 글쓰기라는 개념은 서유럽에서 유래된 접근 방식이죠. 쓰기만이 아니라 읽기, 듣기, 말하기 등을 감각적으로 표현하는 행위가 흥미로웠어요. 제가 써오던 언어를 통째로 뒤집어 다시 배우고 새롭게 사용해야하는 상황 때문에 더 그렇게 다가와요.이 전시에 불턱 공간을 만든 것이 중요했어요. 하이드로 리스닝 워크숍, 리딩서클 워크숍 등을 통해 저 혼자 고민하고 말하는 것보다 다른 사람과 이야기를 나누고 싶은 마음이 컸어요. 하이드로 페미니즘은 물이라는 물질과 몸을 연결된 것으로 다시 인지하게 해주기 때문이죠. 참여자가 서로 몸으로 듣고 머리를 맞대고 쓰고 가까이에서 말하는 것이 하이드로 페미니즘을 이해하는 중요한 방법이 되었어요.

2023.10.22

YE

제주에서 연결된 주제로 하이드로페미니즘 북클럽에 참여한 분들과 언러닝스페이스의 전시와 프로그램을 만들어보고 나니, 루프에서 한 전시가 안전한 공간이였구나는 것을 피부로 느꼈어요. 설치 여건, 위치 같은 표면적인 것보다도, 대부분 서울에서 설아가는 관객과 워크샵 참여자와의 관계에서요. 관객이 들을 준비를 한 공간에서 이야기를 한다는 것, 그 자체가 준비되고 안전한 관계였어요.구좌 전시를 찾는 주민 분이 오면, 전시에 대해 설명해야 하는 범위가 완전히 바뀌어요. 전시 내용을 소개하기 이전에, 왜 예술을 하고, 왜 이것이 필요하는지, 왜 당장 돈이 되지 않는 일을 하는 이유를 질문했어요. 현대 예술이나 전시를 처음 접한 주민은 카페를 연 줄 알았다고 메뉴판을 찾으셨어요. 제주에서 할머니들이 접하는 것은 관광사업이기 때문에, 외지인들을 대상으로 돈을 벌기 위한 행위를 하는 것을 이해하지 못하셨어요.

JY

보통은 어떻게 답하셨어요? 구좌에서 비영리 전시나 예술 활동을 하는 이유를 구좌 주민에게 말하기가 조심스러운 일이에요. 특히 해당 커뮤니티에 관한 예술 활동을 기획할 때는 더 그렇죠. 예술가로서 나와 해당 커뮤니티와의 비평적 거리를 유지하기는 어려워요. 동시에 커뮤니티의 새로운 일원으로 행위해야 하는지, 아니면 예술가 개인으로 그 구성원을 만나야하는지, 그런 윤리적 질문이 반복될 수 밖에 없어요.YE

이것이 저의 ‘일’이라고 설명하기 시작했어요. 해녀분들에게 일, 노동은 궁극적으로 돈을 벌기 위한 활동, 가족을 먹여살리기 위한 책임감이 동반된 것이에요. 하지만 제가 돈을 버는 것이 아니라고 말니까 걱정도 하고요. 제가 느끼는 책임감을 이야기했어요. 내 아이들도 바다에서 수영할 수 있게 오염으로부터 바다를 지키고 싶고, 해녀 삼춘의 대단한 모습을 기록해두고 싶다고 했어요. 예술(가)의 역할, 의미 같은 근본적 질문을 저 혼자 많이 고민하는 계기가 되었어요. 제가 삼춘들 보면서 느낀 것, 엄마랑 이야기하면서 느끼는 것 등 사적인 이야기에서 시작해서, 물과 여성과 바다, 제주에 대한 경험, 관계에 대한 소통을 시도 했어요.루프에서 전시가 끝나고, 지난 여름 해녀학교에 다니며 언러닝스페이스의 전시와 프로그램을 만들어가면서 동네 다른 해녀분과의 더 많은 관계를 만들었어요. 제일 가깝게 지내며 자주 도와드리는 옆집 이웃 할머니는 대부분 80대이세요. 이번 전시를 위해 마을 창고 빌려준 해녀, 해녀학교 인턴 실습을 맡은 해녀 회장 등 젊은 세대 해녀와 소통은 훨씬 수월 하더라구요. 전시에 대해 조금 더 이해하는 부분도 있고요. 세대 차이를 또 한번 느끼며, 상대방의 언어와 내 언어에 대해 언러닝하고 다시 배워야하는 과정이 재미있어요.

JY

젊은 세대 해녀도 젊지는 않으시잖아요. 60-70대인데요.YE

사실 우리 세대끼리 이야기해도 서로를 완벽히 이해하는 것은 아니잖아요. 다른 언어를 사용해도 손짓 발짓 몸짓으로 서로를 이해할 수 있기도 하고요. 관계맺기에서의 차이와 거리에 대해 고민을 더 할 수 있었어요. 제가 하는 일을 완벽히 이해하지 못하는 상황에서 함께 촬영하고 작업하는 경험에서 ‘청자’에 대한 고민을 더 할 수 있어요. 저 혼자 독백하는 것과 할머니와 이야기하는 것, 불특정 다수에게 이야기하는 것, 청자에 따라 이야기의 전달 방식이나 단어를 선택하는 것들이 달라지죠.해녀학교의 마지막 단계는 각자 사는 동네의 어촌계에 들어가 직접 해녀 공동체를 경험하고, 바다의 환경이나 성격에 대해 멘토링을 받으면서 실습하는 것인에요. 저를 맡아주신 해녀회장님이 우연하게도, 제가 살고 있는 집에 사셨던 고이화 할머니의 둘째 며느리에요. 그 분은 고이화 할머니에 대해 다른 종류의 기억을 가지고 있었어요. 돌아가실 때까지 병간호를 하며 고생을 많이 하셨어요. 어머니로서는 아니지만, 해녀로서는 정말 존경할만한 분이셨다 말했죠. 하지만 고이화 할머니는 가부장제에 따라 모든 재산을 장자에게만 물려줬어요. 둘째 아들네는 지금도 그 사실이 서운하고 씁쓸하죠.

JY

존재하지 않던 커뮤니티를 예술 창작을 위해 일부러 만드는 것이 아니었어요. 오랜 시간 커뮤니티가 존재해온 상황에서, 그 안에 들어가서 융화되는 과정 안에서 예술 작업이 변화하고 있어요. 요이 작가가 제주에 오기 전 교류를 했던 사람들과는 너무 다른 커뮤니티를 맞닥뜨린 거죠. 자신이 이해하는 인간에 대한 스펙트럼이 확정되는 과정에서 생기는, 소통의 방법이나 세상을 보는 방법이 넓어지는 과정이 낳는 질문들이 있어요.YE

에피소드가 하나 있었는데요. 올 여름 언러닝스페이스 프로그램에서 어린이, 여행하는 사람, 이주민, 그리고 저희 동네 노년 여성과 전시에 관한 이야기를 나누는 여성적 글쓰기 워크숍을 준비했어요. 노년 여성과 함께 글쓰는 작업, 인터뷰 작업 많이 한 김지승 작가를 초대했어요. 워크숍 같은 행사를 경험하지 않은 분이 대부분이었고, 학교를 제대로 다닌 적이 없어서 글쓰는 것 자체가 불가능한 분들도 많았어요. 그래서 ‘글쓰기’라는 말 대신 ‘물의 말을 나누는 시간’이라 이름짓고 진행하기로 했어요.“삼춘들, 한달 뒤에 9월 24일 금요일 오후 세시부터 네시 한시간 예술 워크숍 할 건데 와주세요~” 라고 하고 저는 캘리더에 입력해 두잖아요. 할머니는 저와는 다른 캘린더에 사니까, 몇 명이 올지 예상 조차 어려웠어요. 여기저기 입소문을 내며 준비를 하는 중, 갑자기 올해 해녀축제에 팔아야 하는 소라의 할당량이 동네마다 생겨서 그 할당량을 잡아야 하는 거예요. 소라 잡기 위해 물질하는 날이 워크숍 날과 겹쳐진 거예요. 예술 워크숍은 우선순위에서 밀려날 수 밖에 없었죠.